How Sentiment Shakes The Market

Once you have satisfied yourself that a company has a solid business model—the subject of our discussion in Beyond the Figures (Canadian MoneySaver, March/April 2013)—then you have to start considering how you, as a potential investor, are going to benefit from the profits which the company will generate.

Once you have satisfied yourself that a company has a solid business model—the subject of our discussion in Beyond the Figures (Canadian MoneySaver, March/April 2013)—then you have to start considering how you, as a potential investor, are going to benefit from the profits which the company will generate.

If, for some reason, you cannot benefit from that stream of future income in the form of dividends or capital gains, then you should not invest in that company but find more fertile ground.

What stands between you and future profits? There are three high hurdles: the market; management; and the unexpected and unknowable.

This article deals primarily with the first of these hurdles, market values, but before getting there, let us briefly consider the other two.

Management has its own interests and just because you are a shareholder does not mean that management’s interests are aligned with yours. Both shareholders and management want to maximize their take from the company and that often puts them at loggerheads over various matters, especially management compensation. As investors, we have to find a way to assess whether this company with an excellent business model also has shareholderfriendly management. If not, we shouldlook for greener pastures. This may sound defeatist but unfortunately the capitalist system has not yet found a solution to rapacious but diligent management.

How do we protect ourselves against the unexpected and the unknowable? The only way is to diversify. Even company directors get surprises about what’s happening down in the bowels of the company. For investors, it is even more difficult. To some extent you can buffer yourself against the unexpected but there is nothing you can do about the unknowable. You cannot even know all that is unknowable.

Luckily, one thing we can do something about is market values.

Two Levels

Public companies operate on two levels. The first is what I call the Profit Machine, which is really the business they operate. The second is the Capitalization Machine at the stock market level, which is where investors decide what companies are worth. (See Figure 1.)

If a company earns $2 per share, and each share trades at $30 on the stock exchange, then its earnings per share (EPS) is $2 and its Price-Earnings Ratio (P/E) is 15.

(P/E) is 15.

EPS is the fruit of the Profit Machine while the P/E ratio comes from the Capitalization Machine because the market is capitalizing on the company’s profit by 15 times.

As the arrows in Figure 1 indicate, both levels feed on each other. The better the company’s earnings, balance sheet and prospects, the higher the capitalization it gets on the market. The higher the capitalization, the higher the price the company can get when it issues new shares and bonds. This means that it will have a cheaper source of finance. The company can therefore expand and produce more profit. This is a virtuous circle.

The opposite of this would be a company in a vicious circle where it is not generating enough profit, has a weak balance sheet with lots of debt compared to assets, and where investors shirk its securities, thus increasing its cost of capital.

A change in the company’s prospects, therefore, is likely to change a company’s capitalization, making it more or less valuable. But this is only one way in which a change in the capitalization rate can happen. The second way, which we will now look at, is nearly completely out of the company’s control.

Enter Sentiment

Sentiment is the colour we see the world. It can be rosy, in which case we are happy and optimistic, or it can be blue, when we are rather sad and pessimistic. Or it can be grey, somewhere in between.

Sentiment is a mental feeling or emotion and Merriam-Webster defines it as “an idea colored by emotion,” or “an attitude, thought, or judgment prompted by feeling.”

We all know what sentiment is, and we all know it is very contagious. People in a crowd are especially susceptible to sentimental contagion but so are the participants in a financial market, bound together as they are by the media, trading platforms, changing market prices, influential opinions and news.

The market is often caught in extreme feelings of dejection or euphoria, and these feelings influence participants’ attitudes and judgments even if there is often no fundamental change in the prospects or fundamentals of a company.

When this happens, prices fall or rise, and investors are willing to buy or sell the same company at a much lower or at a much higher price, according to the mood that takes them.

The reason this happens is because, essentially, a stock is priced on the stock exchange according to its likely future earnings and prospects: when market participants are depressed they don’t believe prospects are good and they are not willing to pay much. But when they are euphoric, prospects are deemed to be great, earnings ever-rising, and prices are bid up, higher and higher, as if they can reach the sky.

Swings And Attitude

Sentiment swings to and fro like a pendulum. Swinging sentiment changes capitalization rates and Price- Earnings ratios and stock prices go up and down-all of this happens instantaneously and continuously.

Often, the swinging is pretty slow and contained within a tight range. In such a state, the market absorbs and digests news comfortably, and nothing unexpected happens. At other times, something important and unexpected comes along (such as a “Lehman event”) and the market gets very agitated, there is a sharp swing in sentiment, and prices move very rapidly–down, in this example.

Suddenly, that good consumer product stock which you have been eyeing but which had a low dividend yield now has a very attractive yield—not because the company did something wrong or its business model failed but just because something bad (and stupid) happened to Lehman Brothers! Companies with great brands and assets can see their stock prices plummet, and still nobody wants them.

You can of course recognize Mr. Market in all of this, the mercurial creature that animates Chapter 8 of Ben Graham’s “The Intelligent Investor”:

- “Imagine that in some private business you own a small share that cost you $1,000. One of your partners, Mr. Market, is very obliging indeed. Every day he tells you what he thinks your interest is worth and furthermore offers either to buy you out or to sell you an additional interest on that basis. Sometimes his idea of value appears plausible and justified by business developments and prospects as you know them. Often, on the other hand, Mr. Market lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes seems to you little short of silly.”

The price of a stock on the stock market should not be seen as the final arbiter of value but only as an indication of what others in the market are thinking and feeling. You can take it or leave it.

Investing is as much about attitude as it is about analysis, and as an investor, you have to disengage your emotions from the market and stand back from it.

You have to try and gauge market sentiment, look at the prices that market sentiment is generating, and decide whether you want to buy, sell or hold, based on your own criteria. Does what you see make sense to you?

Extreme Prices

Mr. Market’s antics sometimes mean that prices can go to the extreme, only to revert back.

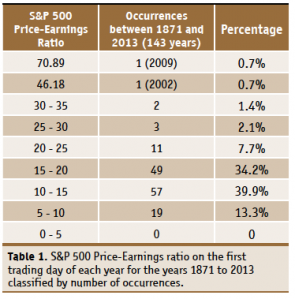

Just to show you how wide these extremes can be, I looked at the Price-Earnings ratio of the S&P 500 at the beginning of each of the years 1871 to 2013, and classified this ratio into the categories shown in Table 1:

First, notice how the P/E ratio was above 10 and up to 20 in 74% of the years. This may be the reason why many investors consider P/E ratios below 15 as attractive and P/E ratios above 20 as pricey.

Second, in 95% of the years, the P/E ratio was between 5 and 25. The wide 5-to-25 range indicates how far apart sentiment can send market values. To buy the same $2 of earnings per share you had to spend $10 when Mr. Market was depressed but $50 when he was having a good time.

Third, the market’s P/E ratio was above 25 in nearly 5% of the years. These high P/Es do not always indicate euphoria. On the contrary, the top two values—in 2009 and 2002—indicate extreme dejection and bad fundamentals.

In 2009, although the S&P 500 dropped to the infamous 666 level in March, the average earnings of companies making up the index fell even more sharply, from around $71 the previous year to less than $14. Since the denominator fell much more than the numerator, the P/E ratio spiked. Similarly, in 2002, after the 9/11 attacks, earnings halved from the previous year and, again, the fall in the index was not enough to compensate for the fall in earnings.

Two details: first, remember that the S&P 500 gives a higher representation to companies with a big capitalization so the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 is only a rough indication to what is happening to the 500 companies which make up the index, and an even rougher indication of what is happening to companies which are not part of the index. Second, we are looking here at the P/E ratio at the beginning of the year. During the year, the variations would be expected to range wider. So, although there were no beginning-of-year P/E ratios between 0 and 5, there could well have been during the respective years.

Is The P/E Useful?

Can you use the P/E to time your buys and sells? The empirical evidence is mixed, although in general the indication is that the P/E ratio does add relevant information to the investment decision.

For example, note that the reciprocal of the P/E ratio is the Earnings Yield, that is, how much each share is earning divided by the price of that share on the market. If the P/E ratio is at 20, then the earnings yield is 5%, which is on the low side. If the P/E ratio is 10, then the earnings yield is 10% which is pretty attractive. P/E ratios of 15 or less, representing earnings yields of 6.7% or more, give some comfort that one is not buying expensively.

I say “some comfort” because not only must we look at the relationship between the P and the E, as we did for the market in 2009 and 2002, but we have to look at many other factors before arriving at an idea of value. A future article might be called “The Tricky P/E”, but for now, suffice it to say that even a stock with a P/E ratio of 30 may be attractive if the company is growing very fast. On the other hand, a company with a P/E ratio of 10 can be very unattractive if it is operating a wasting asset, such as a mine in its final stages. So knowing the P/E can only take you so far.

In order to avoid extreme P/E readings, Ben Graham (and now Robert Shiller) proposed using the 10-year average of earnings per share for E instead of the earnings for one year.

Ultimately, an investor is interested in the return he or she gets. How did capitalization affect your returns? Let’s take a look under the hood.

Your Returns Are Made Of This

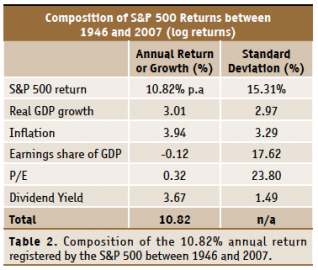

The following table is taken from the book Running Money by Stewart, Piros and Heisler which was published in 2011. The table shows the components of the returns of the S&P 500 for 62 years after the end of World War II.

As you can see, this is a very interesting table.

The compound annual return of the S&P500 over the 62 years was 10.82%. This does not mean that this is the rate you would get by investing in the S&P 500 companies going forward, but in investments, studying the track record and the present situation is often the best we can do, so it is instructive to look at how this 10.82% return was made up.

The compound annual return of the S&P500 over the 62 years was 10.82%. This does not mean that this is the rate you would get by investing in the S&P 500 companies going forward, but in investments, studying the track record and the present situation is often the best we can do, so it is instructive to look at how this 10.82% return was made up.

Economic growth accounted for 3.01% of the return, and inflation even more at 3.94%. Another 3.67% of the total return came from dividends (you despise dividends at your peril!).

The share of company earnings in the economy was nearly flat, at -0.12%; this means that, over the years, company profits made up around the same percentage of the US economy as measured by GDP.

Changes in the P/E ratio only contributed a return of 0.32% and this is less than 3% of the total return of 10.82%. Higher prices in relation to earnings (the much touted “P/E expansion”) did contribute something, but it is very small.

Looking at it in another way, of the 10.82% which the index returned, 7.15% came in the form of capital gains and 3.67% came in the form of dividends. More than half the capital gain was inflation.

The standard deviation column indicates how the returns from these different components varied over the 62 years. A high standard deviation means high volatility. You can see that GDP growth, inflation and dividend yield varied very little, but companies’ earnings as a share of GDP varied quite widely, with a standard deviation of 17.62%, and our friend the P/E ratio varied the most, with a standard deviation of 23.80%.

It’s important to note that this means that the most volatile component of return is the P/E ratio while the most stable is the dividend. This is one of the reasons why I am basically a dividend investor and why we as investors have to watch P/E ratios very carefully when we buy and sell.

The effect of the high volatility in P/E on returns would have been even higher had P/E accounted for a big share of total returns instead of a puny 0.32% but, as nature would have it, the big chiefs are pretty stable while the little guys are all over the place. You can therefore understand why the mandate of central banks is to maintain price stability–imagine the turbulence in equity returns if inflation was highly volatile, and how this would discourage investments.

Mr. Market In Your Pocket

As we saw, the effect of sentiment on capitalization rates is tremendous. We cannot insulate our portfolio from sentiment but we can take some steps to protect it:

- Before you invest, study the fundamentals;

- If you are a long term investor, don’t despise dividends;

- Keep in mind that sentiment is very fickle and can change overnight;

- Swings in sentiment provide you with opportunities to buy and sell–grab them;

- Step back from the market and disengage from its emotions;

- Roughly, historical stock returns were onethird economic growth, one-third inflation, and one-third dividends; and,

- Be cool and logical (remember: good investment is an attitude).

A future article will deal on the various ways in which we can gauge sentiment.

Paul V. Azzopardi BA(Hons)Accy, MBA, FIA is a Portfolio Manager and an Instructor at the School of Continuing Studies, University of Toronto, where he presents the “Choosing Income Investments” course in the Fall at the Mississauga campus and in the Spring at the St. George, Toronto campus.

The opinions expressed here are not investment advice and are solely Paul’s and not those of his employer's.