Why “Buy Low And Sell High” May Not Be The Best Investment Strategy

We’ve all heard that successful investing happens when you “buy low and sell high”, but I encourage you to challenge that approach and implement an alternate investment strategy. Here’s why:

The Problems With Buy Low And Sell High

There are several issues with trying to buy low and sell high, the operative word being “trying”. First, we don’t know when investments are at their lowest, nor do we know when they are at their peak. This leaves you having to bet on lows and highs. Not only could this approach be stressful and time-consuming, but there is a risk that you may be wrong.

Even if you are right, and you buy stocks at their lowest lows and sell them at their highest highs, this strategy would require you to hold cash while you wait for stocks to go low. Holding cash has an opportunity cost because you can’t be fully invested while you wait on the side-lines for stocks to go low enough to buy them. Holding cash instead of being invested results in missed income or dividends you would otherwise have earned if that cash was invested.

Further, if you do successfully sell investments when they are high, after you’ve sold them, you’re left with uninvested cash, and the opportunity cost of holding that cash while you wait for another low. Buying low and selling high requires you to try to time the market. And I would suggest that time in the market will lead to greater success than timing the market.

Time In The Market

The value of an investment after a certain amount of time in the market is easy to calculate, with some assumptions:

- The present value of your investment, or cash you would invest now (known)

- The rate of return you’ll earn (which you have to assume)

- The time it will be invested.

- You may have seen this expressed as FV=PV(1+i)n.

Knowing how much cash you have to invest today, and assuming you invest it all, you can estimate how much you’ll have in the future if you accurately assume the rate of return. (While past rates of return do not guarantee future results, you can consider them to estimate the rate of return for this calculation). In this scenario, your present value and timeframe are known, meaning you’re only estimating the rate of return or one of three inputs.

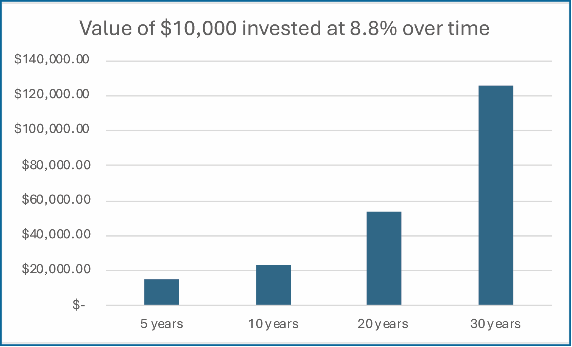

Visually, here is the value of $10,000 (today’s investment) invested at an assumed 8.8% return over various timeframes between five and 30 years.

Timing The Market

Timing the market, on the other hand, requires you to make more assumptions, as you have to assume both the rate of return, and also the time in the market. This is because the time spent waiting for investments to go low enough to buy does not count as time in the market. Therefore, you’re forfeiting the known variable of time in the market in the hopes that the rate of return will increase.

The risk is that you miss the best days in the market, which can be costly.

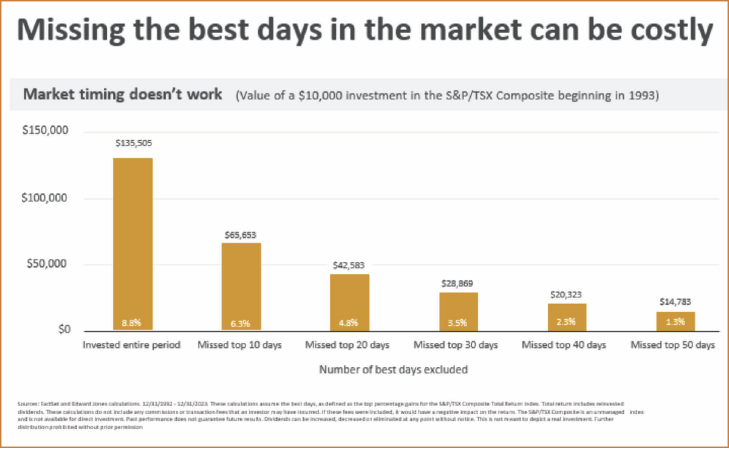

The chart below illustrates the value of being fully invested (on the left, with an average annual return of 8.8%), and the impact on the same investment, had you missed out on the best days in the market. The more of the best days you miss out on, the greater the impact on your overall investment return.

Over this 30-year period, missing only the best 20 days in the market could have cost you over $90,000 in gains, or half of your potential returns.

An Alternate Approach

Start with why. Consider your goal(s) and the reason you’re investing, whether it’s retirement, sending a child to post-secondary school, a vacation, or a new home. Determine the cost of the goal and then figure out how much you’ll need to invest now (your present value), or at what cadence and at what rate of return to meet that goal.

We can use the present value formula above and turn it into a future value formula: FV=PV*(1+r) n., which uses the same inputs as the Present Value calculation but works backwards. Working backwards will help you determine how much to invest now to get where you need to be when you want to be there.

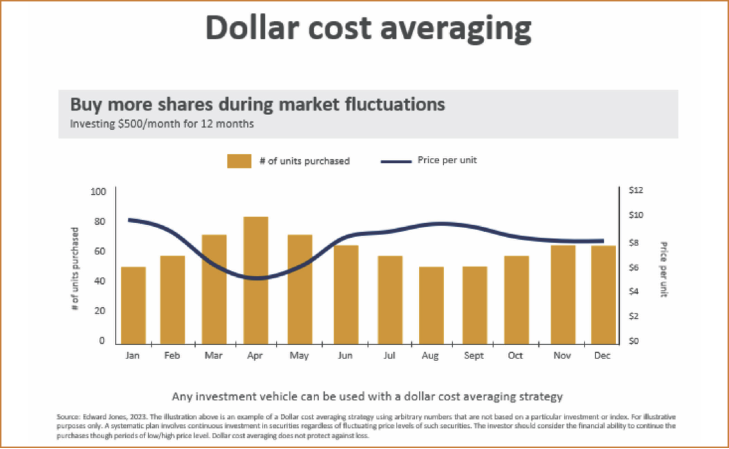

Then, put your investments on autopilot. Automatic investing results in you buying investments when they are both low and high, known as dollar-cost averaging. You invest the same dollar amount, which results in you buying more shares of an investment when the cost is low, and fewer when the cost is high. It looks something like the chart below, "Dollar Cost Averaging".

This approach focuses on what you can control: the amount you’re investing and the time it will be invested. It takes the emotions and waiting on the side-lines out of investing and saves time and transaction costs. It will ensure you don’t miss the best days in the market, and that you fully participate in income and dividends. But most importantly, it’s a plan to help you focus on why you’re investing rather than just the fact that you’re investing and allows time in the markets to work in your favour.

Julie Petrera, MBA, CFP, CIM is a certified financial planner.

X: @petrerajulie