Tipping Point - Investing In The War Against Obesity

Tam-Tam: Tasty Profits From Pure-Play Pharma

In Yiddish, tam means “taste”, both literally and metaphorically. In business TAM means “total addressable market”. It is one of the metrics used to assess the potential profitability of a business. For investors in pure-play pharma companies specializing in anti-obesity drugs, it is proving to be tam-tam: very tasty on both fronts. The TAM for weight loss drugs is massive, with over 750 million clinically obese people worldwide—over 40% are adults and one-in-five are children in the United States. It’s also tam, because leading pharma companies such as Denmark’s Novo Nordisk and America’s Eli Lilly, are generating tasty gains for investors.

The new class of hormonally based drugs called GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1), which contain the active ingredient semaglutide, act as intermediaries between the brain and the gut, and they help to regulate blood sugar levels. As it turns out, they also regulate other functions such as food cravings, appetite, satiation, impulse control, and reward sensations, among others. First approved in 2005 to treat diabetes, they are now also being prescribed by the bucketful to non-diabetics who seek to lose weight and keep it off, something that is notoriously difficult to achieve. These drugs, sometimes called the “Artificial Intelligence (AI) of healthcare”, have upended medical and cultural assumptions about obesity. They have the potential to transform millions of lives for the better. But their efficacy and growing popularity is having knock-on effects on a wide range of industries such as fast-food, consumer goods, medical appliances, and certain specialized surgeries, not to mention the legacy weight loss industry which generates billions of dollars annually through supplements, meal plan suppliers, and memberships. Who will be the winners and the losers in the battle against the bulge?

Heavy Weights: The “King Kongs” Of Anti-Obesity Drugs

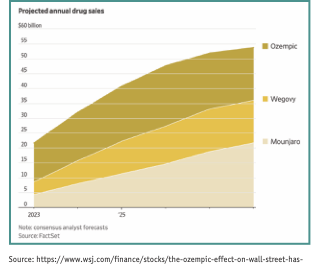

Both Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have been two of the strongest performers in the large-cap pharma space. As the leading pure-play pharma companies based on their stable of diabetes and obesity drugs, share prices of both companies have doubled in the past three years. Thanks to its diabetes and obesity portfolio comprising Ozempic and Wegovy, Novo Nordisk was Europe’s most valuable company by market capitalization in 2023. Sales of Wegovy grew 737% and Ozempic sales grew by 56%. At year-end, the company raised its guidance on sales and operating profit growth to 33- and 46-per cent, respectively. Revenues grew 25% to 176.95 billion DKK.

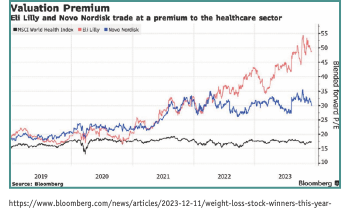

Its competitor Eli Lilly, maker of Mounjaro which is sold under the brand name Zepbound, received FDA clearance in November 2023 for use as an anti-obesity medication, although it was already being used off-label for this purpose for some time. Sales are projected to grow over 856%, year-over-year. Valuations for both companies trade at a premium to the general healthcare sector as measured by the NYSE Arca Pharmaceutical Index. (For example, Eli Lilly trades at 44-times forward earnings vs. 15 for the Index.) While projections for future growth and profits of $100 billion look terribly appealing, analysts point to some clouds in the coffee.

Tight Supply

In the face of skyrocketing demand for the drugs, both companies have been forced to restrict access to ensure existing patients with diabetic and/or obesity issues can fill their prescriptions. In the meantime, they are frantically working both internally and with third-party suppliers to increase capacity. However, building new factories and vetting trusted partners takes time. Growth prospects will continue to be hampered until drug volumes can be reliably increased. All three drugs—Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro—are injectibles which are more complicated to manufacture than pills. To keep the weight off, patients must continue to take the drugs–at lower dosages–or the weight gain will return.

Growing Competition

In the meantime, salivating at the potential for the enormous profits in this segment of the pharmaceutical industry, other drugmakers are rapidly testing new therapies. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, there are currently more than 50 anti-obesity drugs in development from 40 companies. Many of these are exploring other hormones in addition to GLP-1 to achieve weight loss without the loss of muscle mass or to eliminate some of the other unpleasant side effects of the current medications such as vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort and kidney and thyroid problems.

A report by Morgan Stanley projected the global anti-obesity market would be worth US$77 billion by 2030. As one chief executive of pharma start-up Phenomix Sciences said recently, “It is almost as if a completely new disease has been discovered that just happens to have 100 million people with it.”

Due to the difficulties of obtaining the drugs—including supply issues, the high cost, uneven insurance coverage, eligibility hurdles, scheduling regular clinic visits, and fear of needles, only a small fraction of those who want to take the drugs are currently taking them. New, lower cost anti-obesity therapies, and those based on pills, are likely to turbo-charge demand further—and present competition to the incumbents.

Fat Cats: High Drug Costs

There is a simple reason it’s been the A-list celebrities and not your neighbourhood dry cleaner touting the astounding benefits of anti-obesity drugs: These drugs are pricey. The annual cost for Ozempic is similar to the price of an entry level Hermes Birkin, around US$10,000. In December last year, Oprah Winfrey showed off her new, svelte shape and admitted she was taking a weight loss drug but did not disclose which one. Not all insurance companies cover the cost of the medications, although employees of Novo Nordisk get free access to Ozempic as a company perk.

Side Dishes: Collateral Damage Or Contrarian Bet?

As demand for anti-obesity drugs soars, investors worry that industries which abet and benefit from the rise in obesity such as fast-food restaurants, snack makers, and medical device manufacturers would suffer. Because the drugs lower the set point for satiation, they reduce food and alcohol cravings. They also increase a preference for healthier, less processed foods. And, because obesity often leads to cardiovascular, endocrine, and orthopaedic problems, a population that is less obese will need fewer knee and hip replacements, bariatric surgeries, and heart valve and stent implants. This is bad news for McDonald’s, Krispy Kreme, and Medtronic, not to mention WeightWatchers. Or is it?

While there has been a drop in demand for bariatric surgeries, according to Medtronic’s chief executive, as more people opt for taking the drugs, other companies, such as Walmart, Rite Aid, and Kroger are enjoying the benefits of the extra foot traffic as people come in to fill their anti-obesity med prescriptions and then make other purchases while in store. Executives predict that the new drugs will increase consumer interest in healthy meals and supplements, and health and wellness items in general which should grow sales in the long run.

Contrarian investors point to the doomsday scenario in 2003 when the popularity of the low-carbohydrate Atkins Diet led to a 30% drop in McDonald’s share price as investors fled the carb-centric, fast-food industry. Instead, buying McDonald’s shares at the then price of $30 would have been a wise investment. (Today it trades at $287.) Companies that rely on only one sugary or fatty, or sugary-and-fatty product, like Krispy Kreme, are more likely to be impacted than battle hardened survivors like McDonald’s or Nestlé which can adapt their offering to the times. As for WeightWatchers, or W. W. International, as it is now called, a company that counts Winfrey as a shareholder and board member, it recently spent US$106 million to acquire Sequence, a tele-health company that prescribes anti-obesity drugs. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Rita Silvan, CIM is a finance journalist specializing in women and investing. She is the former editor-in-chief of ELLE Canada and Golden Girl Finance. Rita produces content for leading financial institutions and wealth advisors and has appeared on BNN Bloomberg, CBC Newsworld, and other media outlets. She can be reached at rita@ellesworth.ca.