Death Of A Taxpayer – Part Four

Nine years ago, MoneySaver published Brian’s four-part article dealing with the death of a taxpayer. In this edition, we continue the running of an updated version of the article.

Lana, Editor-in-Chief

This is the final article dealing with the death of a taxpayer. Part one presented the income tax implications of death, part two dealt with special income tax rules for paying the deceased’s income tax liability as well as capital loss utilization in the year of death and part three focused on the mandatory and optional separate personal income tax returns to be filed for a deceased taxpayer.

This article deals with strategies to minimize income tax due on death: some strategies for the taxpayer to do while alive and some for the estate trustee to consider after the taxpayer’s death.

Early Inheritances

The less wealth an individual has at death the less exposure they have to income tax at death. If the plan is to pass assets to children, why not do it now? The kids may prefer the money now rather than later, especially if they have a mortgage. Where cash is given to an adult child there are generally no income tax implications. (Canada does not have a gift tax.) If marketable securities are sold to fund the gift, capital gains can result that are subject to income tax in the year of sale. However, this income tax may be less than the income tax that would be due on the individual’s death.

If there is worry about how the adult child will use the money—or perhaps family law concerns —an interest-free loan can be made to an adult child rather than an outright gift. This offers the parent the ability to “call” the loan if need be. The loan can be forgiven in the parent’s Will with no income tax implications to the parent or adult child.

Employment

An individual can negotiate with their employer to pay a $10,000 death benefit on passing (whether still employed or not). The surviving spouse (which, for income tax, includes a common-law spouse) can receive this tax-free.

Pass Assets To Surviving Spouse ñ Or Perhaps, A Spousal Trust

Where non-Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSP)/Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF)/Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSA) held assets are passed to a surviving spouse on death the accrued gain (and/or recapture) is not triggered, so no income tax is payable. This is also true if the assets are passed to a testamentary spousal trust.

The use of a testamentary spousal trust has the advantages:

- The trustees of the trust can assist the surviving spouse in managing the assets.

- It can provide some protection to the ultimate beneficiaries of the deceased’s estate— e.g., the children of the deceased—so that the remaining assets unused by the surviving spouse will be passed to the children and not to others (which could occur if the surviving spouse were to remarry or has children from a prior marriage).

On the death of the surviving spouse the spousal testamentary trust will be subject to income tax on the accrued gains/recapture of the assets at that time. This is the same implication as if a spousal testamentary trust had not been used and the spouse had received the assets directly.

RRSPs And Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs)

When RRSPs and RRIFs are passed to a surviving spouse no income tax is payable on the death of the first spouse. It is best that the documents at the financial institutions holding the RRSPs and RRIFs note that the spouse is the beneficiary of the plans.

If, on death, the deceased has unused RRSP contribution room—and a spouse who is under 72—a post-death spousal RRSP contribution can be made, and an income tax deduction claimed on the final personal income tax return of the deceased.

If there is a concern in having a large income tax liability on death and the individual is not currently subject to income tax in the higher income tax brackets, the individual can withdraw extra from the RRSP or RRIF to increase their annual taxable income and income tax liability. The extra income tax paid early may be less than the income tax paid on death where a significant amount of taxable income may be subject to income tax in the higher tax bracket.

The 2020 (federal only) income tax brackets are:

|

Income tax rate |

Taxable income |

|

15% |

Up to $48,535 |

|

20.5% |

$48,536 to $97,069 |

|

26% |

$97.070 to $150,473 |

|

29% |

$150,474 to $214,368 |

|

33% |

Above $214,368 |

Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA)

On death, a TFSA retains its “tax-free” status and no income tax is payable by the deceased. If the surviving spouse is named the successor holder of the TFSA, the funds can be transferred to the surviving spouse without affecting the spouse’s TFSA contribution room. The TFSA of the deceased continues to exist and the income earned in the plan after the date of death is not taxable to the surviving spouse.

When the spouse is not named as a successor holder, but is named a beneficiary, the spouse may still receive the deceased’s TFSA funds tax-free and contribute those to their own TFSA without affecting their TFSA contribution room. This is referred to an exempt contribution.

TFSA beneficiaries other than a spouse, such as an adult child, cannot make an exempt contribution. Any funds received can be contributed to the beneficiary’s own TFSA subject to the beneficiary’s own TFSA contribution room.

Capital Gains Exemption

If an individual owns shares in a qualifying small business corporation or qualified farm or fishing property, they can take advantage of the exemption now by locking in—or crystallizing—the accrued capital gain. The capital gains exemption in respect of shares of a small business corporation is $883,384 (2020) and the exemption for a farm or fishing property is $1,000,000.

Once this is undertaken the individual no longer needs to worry about maintaining the investment so that it continues to qualify for the exemption, or the income tax rules being changed.

If an individual does not make use of a capital gains exemption before or on death it is lost. It cannot be passed to a beneficiary.

Locking In The Income Tax Liability On Death

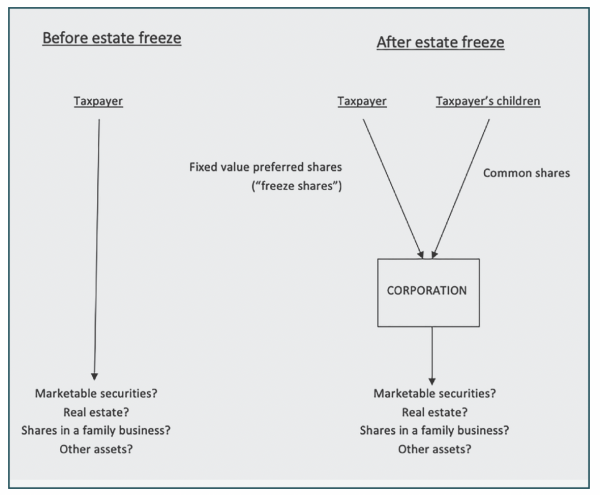

As an asset grows in value so does the accruing income tax liability associated with the asset. If an individual exchanges a growth asset (say, a portfolio of marketable securities or real estate, shares of a family business, etc.) for a non-growth asset (such as a preferred share of a holding corporation) the income tax faced by that individual on that asset will stop increasing.

The individual needs to transfer their growth asset to a corporation in exchange for fixed value preferred shares. No income tax on the accrued gain is triggered on the exchange and the payment of the income tax is deferred until the death of the individual. This is referred to an estate freeze as the income tax bill is frozen.

At the time of the freeze the eventual income tax liability can be calculated, and plans put in place to ensure funds are available when the income tax liability becomes due.

As the value of the preferred shares are fixed or capped, the growth of the asset, after the exchange—the freeze—will accrue to the value of the common shares of the holding corporation. These shares will be owned by the individual’s heirs (e.g., adult children) and not the individual.

As the common shares are not owned by the individual, they are not part of the assets exposed to the deemed sale income tax rule on death. Therefore, no income tax liability is faced by the individual on death on the post-freeze growth of the asset.

Life Insurance

The death benefit of a life insurance policy is received tax-free. Life insurance does not decrease the income tax due at death but provides a way to fund the income tax liability of the deceased.

The strategy is attractive where a family cottage would need to be sold to obtain cash to pay the income tax on its accrued capital gain. Consider having the eventual beneficiaries pay the premiums as they are the ones who will ultimately benefit.

Post Death Losses

An estate will incur a loss on an asset it sells where there is a decrease in value after the deceased’s death. Where the loss is incurred in the first taxation year of a graduated rate estate (discussed below) an income tax election can be made to claim the loss on the final personal income tax income tax return of the deceased.

This election can be made on losses resulting from both assets that are capital property (e.g., shares of public and private corporations, mutual funds, etc.) and assets that are depreciable property used for rental or business purposes (e.g., rental building). To maximize the availability of this election it is best the first taxation year end of the graduated rate estate be a full 365 days after the death.

When there is a post-death decrease in value of an RRSP or RRIF before the plan is wound-up and distributed to the estate, the loss can be deducted on the final personal income tax return of the deceased.

Medical Expenses

A taxpayer, while alive, can claim medical expenses incurred in any 12-month period that ends in the year for which the income tax return is being prepared for. This offers the taxpayer flexibility in determining the best 12-month period to maximize the income tax credit resulting from medical expenses.

In the year of death, the period is extended to any 24-month period that includes the date of death. This permits the claiming of medical expenses on a deceased’s final personal income tax return that may have been paid after the deceased’s death.

Charitable Donations

While alive, and on death, it is preferable to donate publicly traded marketable securities to a charity rather than selling the securities and donating the cash. When the securities are donated, the accrued capital gain is not subject to income tax. The charity will issue an official receipt noting the value of the securities donated for which an income tax credit can be claimed.

Many taxpayers include gifts/donations to charities in their Wills. The actual donation to the charity may not occur until months after the taxpayer’s death. However, a special income tax rule permits that a charitable donation made after a taxpayer’s death, by virtue of a Will, can be claimed on the deceased’s final personal income tax return. When publicly traded securities of the deceased are donated to a charity after death, the securities are not subject to the deemed sale income tax rule at death.

Further income tax provisions permit that the amount of charitable donations claimed in the year of death, including those made after death by virtue of a Will, can be as high as 100% of the net income (line 23600 on a personal income tax return) reported by the deceased in their final personal income tax return. (This is restricted to 75% when a taxpayer is alive.) If the deceased’s charitable donations in the year of death exceed 100% of the deceased’s net income, the excess can be claimed on the deceased’s income tax return for the year prior to the year of death (up to 100% of the net income reported in that year as well).

Graduated Rate Estate

To ensure the special rules concerning charitable donations made after the death of the taxpayer can be taken advantage of, the estate trustee must ensure that the donation is funded by the graduated rate estate (GRE) of the deceased taxpayer. A GRE of a deceased can only exist for 36 months after the death. For income tax purposes, an estate is treated as a trust. Where multiple trusts were set up by the Will of the deceased, only one trust can be designated as the GRE.

Graduated rate refers to the ability of the estate to take advantage of the graduated income tax rate brackets in calculating its income tax liability. (These brackets are the same income tax rate brackets that individuals use.) Where the graduated income tax rate brackets are not available to be used, all the taxable income is subject to income tax in the highest income tax rate bracket.

Brian J. Quinlan, CPA, CA, CFP, TEP

Campbell Lawless LLP,Chartered Professional Accountants

bjq@clcpa.ca