Tax Planning For Your Investments

Tax-smart strategies are a sure-fire way to boost investment returns. Asset allocation and fees are also important, but tax is a key factor impacting investors that can be controlled by them.

Tax-smart strategies are a sure-fire way to boost investment returns. Asset allocation and fees are also important, but tax is a key factor impacting investors that can be controlled by them.

Tax strategies for investments depend in large part upon the type of investment account in question.

Tax Free Savings Accounts (TFSA)

TFSAs can serve a dual purpose. They can act as an emergency fund for a savings account so that what little interest income is being earned these days is at least tax-free. But they may be better suited for long term investing, particularly now that the cumulative TFSA limit since 2009 has grown to a healthy $63,500.

If someone is in the fortunate position to be able to maximize their TFSA contribution every year, and particularly if they may not anticipate needing withdrawals soon, or ever, their TFSA should be as aggressive as possible. For some, this may even mean 100 per cent in equities, in order to maximize tax-free growth. Fixed income investments could instead make up a larger proportion of other accounts like Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs), where withdrawals are anticipated.

Not all TFSA income is tax-free, however. Foreign dividend income earned in a TFSA will generally be subject to withholding tax, even if that foreign dividend income is earned through Canadian Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) or mutual funds. This does not mean investors should not hold foreign investments in a TFSA, since diversified geographical exposure is important. But in some cases, foreign stocks, especially those with a high dividend, may be better held in other investment accounts.

Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP)

RRSPs can be a good place to shelter U.S. dividend income from tax. U.S. stocks and U.S.-listed American equity ETFs held in an RRSP have no tax withheld on their dividends. Keep in mind that Canadian-listed U.S. equity ETFs will have U.S. tax withheld. An RRSP holder needs to hold U.S. stocks directly or by way of ETFs listed on U.S. stock exchanges to avoid withholding tax.

Buying U.S. stocks and ETFs introduces foreign currency transaction costs to move Canadian dollars into U.S. dollars. When investing for the long term, the initial cost may be well worth it. Strategies like Norbert’s Gambit can help reduce foreign exchange costs to buy U.S. dollars.

Despite being a good place to hold U.S. stocks, RRSPs may in some instances be a better place to hold fixed income investments. Investors often think having a large RRSP is a good thing—the sign of a saver well poised for retirement. Because RRSP withdrawals are taxable, some retirees will lose up to 62 per cent of their RRSP withdrawals to income tax (high income retirees subject to Old Age Security clawback in Quebec are the highest taxed personal taxpayers in the country). And on death, up to 54 per cent of an RRSP can disappear to tax if it is not left to a surviving spouse (7 provinces have top tax rates exceeding 50 per cent).

This does not mean RRSPs are not a good tax strategy, as they are well worth it for contributors with moderate or high tax rates during their working years. It just means if there is the option to grow an RRSP, a TFSA, or a non-registered account with aggressive investing, an RRSP may be the last place to swing for the fences.

If an investor has fixed income exposure, as most do, an RRSP is usually the best place to hold it. Also, RRSP withdrawals in retirement, even well before age 72, may be a good decumulation strategy. When approaching retirement, and actively withdrawing from investments, fixed income should probably be part of any account that is being drawn down.

Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF)

For a young retiree, early RRSP withdrawals prior to age 72 often make sense. An RRSP does not need to be converted to a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) to take withdrawals. An RRSP that is being drawn upon should probably be converted to a RRIF by age 65, and the reasoning is two-fold.

RRIF withdrawals after age 65 qualify for the pension income amount, which is a tax credit for up to $2,000 of eligible pension income. Defined Benefit (DB) pension income qualifies, but Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS) pensions do not. RRIF withdrawals are considered eligible pension income after age 65 and withdrawing at least $2,000 can result in tax savings ranging from $351 to $449 depending on a retiree’s province or territory of residence, often making this $2,000 completely tax-free.

Another benefit of converting an RRSP to a RRIF is the ability to split RRIF withdrawals with a spouse or common law partner after the age of 65. A pension income splitting election can help allocate income between spouses and minimize a family’s tax bill.

Strategies for investment assets in a RRIF account are much the same as the approach with an RRSP, though the merits of fixed income once a registered account is being drawn down are that much more enhanced.

Non-Registered

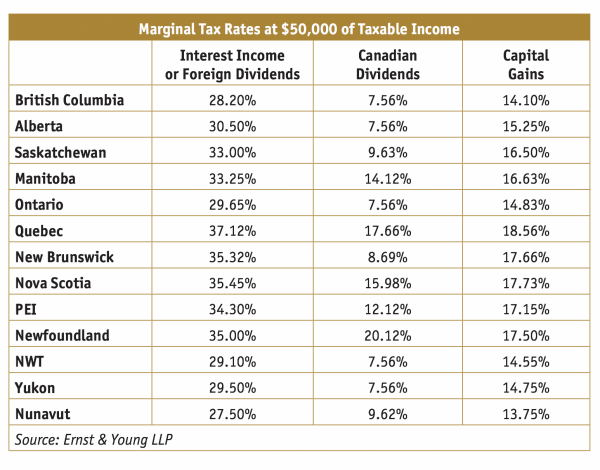

Investors are generally best to maximize TFSA and RRSP contributions before investing in a non-registered account. Understanding some of the tax strategies with non-registered investing needs to start with understanding the marginal tax rates payable on different types of investment income.

Capital gains and Canadian dividends are taxed at more favourable rates in a non-registered account than interest and foreign dividends. Tilting a non-registered account towards stocks, and particularly Canadian stocks, can help save tax.

Asset allocation should always be considered as well though, and particularly if a non-registered account is large relative to other accounts, it should include foreign stocks to be well diversified.

Also, if the time horizon for a non-registered account is short, or the account is being drawn down heavily in retirement or the funds are expected for a near-term expense, there should be an allocation towards fixed income.

A common criticism of holding Canadian stocks for retirees is the way in which Canadian dividends are taxed. The dividends are grossed up by 38 per cent, such that $1.38 of income is reported by a taxpayer for every $1.00 of Canadian dividend income earned. There is an offsetting tax credit—the dividend tax credit—that reduces income tax payable accordingly and results in a lower overall tax rate than foreign dividends. This gross up treatment is often criticized for increasing the clawback of an OAS recipient’s pension, which happens if 2019 income exceeds $77,580. High income OAS pensioners have 15 cents of every dollar of OAS income clawed back for income over $77,580.

OAS clawback is therefore 5.7 per cent higher—15 per cent of 38 per cent—for every dollar of Canadian dividend income versus foreign dividend income. However, foreign dividend income is taxed at roughly 12 to 24 per cent higher than Canadian dividend income for an OAS recipient. Despite the increased OAS clawback from investing in Canadian stocks, it still means a lower overall tax rate for high income retirees.

Year-end tax planning advice for non-registered investors often includes a discussion of tax loss harvesting. This is a process whereby deferred capital losses are triggered in order to offset realized capital gains, whether those gains are in the current or previous years. If a taxpayer has a net capital loss for the current year, it can be carried back up to three years to offset previous taxable capital gains and generate a tax refund. Otherwise, capital losses can be carried forward indefinitely to use against future capital gains.

Tax gain harvesting can also be an exercise worth considering, however counterintuitive. Rather than allowing large capital gains to be taxed at a high rate in a single, extraordinary year, a non-registered investor may consider strategic realization of small capital gains over time. As an example, if an investor realizes a $10,000 capital gain over two years instead of one, they may be able to keep their income in both years in a lower tax bracket. Particularly for those over the age of 65, subject to OAS clawback, a jump in income can cause their next dollar of income to be taxed at a 15 per cent higher tax rate, or more. Realizing a capital gain a year earlier may cause tax payable a year earlier, but that could mean over a 15 per cent after tax annual return.

Income planning and investment decumulation can be as much art as science, but the point is it can be worthwhile trying to plan your income in the current and future years as best you can.

Another consideration, especially for high income seniors, is the potential of a family trust. Without getting too in depth, an inter vivos trust could be a way to legitimately move investment income from a high income grandparent’s tax return onto their low or often zero income grandchildren’s tax returns. Trusts can make sense for parents as well, but grandparents are more likely to have significant non-registered assets, and more young, low income, minor family members they want to provide for financially.

Summary

In closing, tax matters, and not just on April 30, and not just this year. Tax planning for the long run for your investments can help boost returns, increase retirement income, and maximize an estate.

Jason Heath is a fee-only, advice-only Certified Financial Planner (CFP) at Objective Financial Partners Inc. in Toronto, Ontario. He does not sell any financial products whatsoever.