Yes, Bonds Are Still An Important Part Of A Portfolio

Now that the U.S. Federal Reserve (FED) has decided to increase interest rates and expects three more rate increases in 2017, investors may be seeing red in their year-end investment statements. While seeing capital losses on a statement is not welcome in any form, investors may be dismayed to see it is from an asset class typically viewed as a stable source of income. Fixed income, also known as bonds, may be showing losses (or at least declines in value) in the statements that many individuals receive at year-end, and those losses may only get larger over the year. While the initial reaction will be to dump fixed income amidst high probability losses, bonds are still a necessary part of a portfolio.

Now that the U.S. Federal Reserve (FED) has decided to increase interest rates and expects three more rate increases in 2017, investors may be seeing red in their year-end investment statements. While seeing capital losses on a statement is not welcome in any form, investors may be dismayed to see it is from an asset class typically viewed as a stable source of income. Fixed income, also known as bonds, may be showing losses (or at least declines in value) in the statements that many individuals receive at year-end, and those losses may only get larger over the year. While the initial reaction will be to dump fixed income amidst high probability losses, bonds are still a necessary part of a portfolio.

After decades of continued declining interest rates (and in turn rising bond prices as the two tend to move inverse to one another) many long-term holders of fixed income have become accustomed to some sizable capital gains in addition to a steady income flow. This trend looks like it is ending, as the interest rate path finally appears to be on the upswing in the U.S. This means, as interest rates rise, bond prices will fall and those capital gains in portfolios will also decline. Not only will this be an uncomfortable feeling for investors who have enjoyed the ride up, it will be in an asset class that ‘promises’ stability and low but steady returns. So any enterprising investor may conclude that if higher interest rates mean lower bond prices and in turn losses in fixed income going forward, they should just be sold out of a portfolio, right? Not so fast! While the return outlook is unlikely to be overly exciting, bonds still hold an important place in an investor’s portfolio as that investor approaches retirement. To be clear, we are not bond ‘bulls’ by any means but have seen increased questions from our membership along the lines of ‘Bonds are only going down, should I sell them?’ When this happens, sentiment may be shifting too far in favour of other asset classes and the case for less loved but still important assets should be made.

The Devil You Know

There is real value in certainty, especially when it comes to investing. This is what bonds provide. Even if an individual is guaranteed a 2% capital loss a year (mind you, the income return could more than make up for this), someone in retirement can plan accordingly with the understanding that this loss will occur. With equities, you don’t know what you are going to get year to year. While the long-term returns should be much greater, investors do not know when those returns will occur. If you are in retirement and need that money now, you do not have the time to wait a few years for markets to turn around. The stability and higher level of certainty that bonds provide has true value that an investor does not get from stocks.

Psychological Hurdles

Seeing account values decline in terms of capital can be tough, but investors often forget to include the distributions that assets pay in return calculations. So while the value of a bond may be decreasing, the total return when including distributions could more than offset the losses. The key metric to pay attention to in this case is yield to maturity (YTM). The YTM is the total return an investor can expect to receive from a bond if held to maturity. While a bond can trade at a premium (and lead to a loss on expiry), the distribution can still create a total gain and in turn a positive YTM. So it is important that an investor look past simply the capital gain or loss and consider the distributions received over the life of the asset.

Better Source Of Cash

In line with comments on yield to maturity, bonds are simply a better alternative to cash as they will still generate a positive total return. Cash guarantees investors to lose money to inflation. Bonds will at least offer a meagre return. Further, bonds can still be viewed as a source of cash. If the next financial crisis or some other pullback in the markets occurs, there is no reason a bond allocation couldn’t be viewed as a source of cash for rebalancing into unloved or underpriced assets.

Withdrawing From A Portfolio In A Downturn Is A Wealth Killer

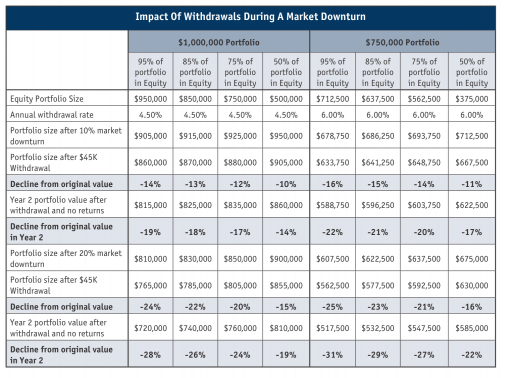

If an investor eschews bonds in favour of equity, there is potential for material wealth destruction if a downturn does occur at some point. We have outlined two portfolios, one worth $1,000,000 and another worth $750,000 with each portfolio showing different equity weight scenarios. The analysis considers the impact of a market downturn at the varying levels of equity when withdrawing $45,000 from the portfolio. The analysis considers two downturn scenarios where markets decline 10% and 20% in the first year then are flat in the second year. Withdrawals of $45,000 are made in both years. The chart below looks a bit difficult to digest but it is worth taking a few minutes to grasp it.

We think there are a few noteworthy points to make here:

- A 10% downturn and flat market for another year are not unreasonable scenarios while a 20% downturn is possible any given year

- A before tax withdrawal rate of $45,000 is not an aggressive assumption

- The analysis does not include fixed income returns (no returns assumed), meaning in a downturn scenario, those with more fixed income would likely fare even better than indicated

- It also assumes the investor does nothing during the downturn (i.e. sell equities at the bottom). The more equity held in the portfolio, the more likely the investor will sell at the wrong time in a downturn.

In addition to the points above, we think there are a few key takeaways:

- The larger a portfolio and less equity held, the less an investor feels any impact from a downturn.

- Portfolio size matters – Larger portfolios have more of an ability to weather any storms while the constant value of withdrawals (living costs likely can’t change) has a bigger proportionate impact on the smaller portfolios. Additionally, larger portfolios can withstand ‘more years’’ worth of downturns while smaller portfolios have less flexibility. This leads to psychological pressure while investing. Put simply, the smaller the portfolio, the less room for error and/or risk.

- In the extreme scenarios, a third of an investor’s life savings can be eliminated in two years.

- Using a $1 million portfolio, at a 7% assumed total return going forward and with the same annual withdrawal, it would take 11 years to make back the money in the 10% downturn scenario with 95% equity. It would take eight years under the 50% equity scenario.

- Using the $750,000 portfolio, across all scenarios using the same withdrawal rate, an average of 7% returns would not be enough to offset the withdrawals and the portfolio size would be in continual decline. While the portfolio would be large enough to support retirement needs in most cases, it would be very unlikely to reach historical portfolio values.

Ryan Modesto, CFA, is Managing Partner at 5i Research Inc. in Kitchener, Ontario. He can be reached at ryanmodesto@5iresearch.ca