The True Cost Of Tax Inefficiency

When investors run out of contribution room in their tax-sheltered investment accounts, such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) and Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs), they often continue investing in a non-registered investment account, which unfortunately does not provide the same automatic benefit of avoiding or deferring taxes. Managing investments in a taxable portfolio then becomes a much more complicated exercise—one that attempts to maximize wealth on an after-tax basis instead of a pre-tax basis, which is how investments should be structured in a registered account.

When investors run out of contribution room in their tax-sheltered investment accounts, such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) and Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs), they often continue investing in a non-registered investment account, which unfortunately does not provide the same automatic benefit of avoiding or deferring taxes. Managing investments in a taxable portfolio then becomes a much more complicated exercise—one that attempts to maximize wealth on an after-tax basis instead of a pre-tax basis, which is how investments should be structured in a registered account.

Any investment income that is earned in a non-registered account is subject to taxation annually. Those taxes can be thought of as an annual “fee”, similar to the investment management fees charged by a financial institution or advisor. But unlike investment management fees, which should be easy to identify and compare amongst different investment options, every investor will have their own specific tax rates to consider and the actual cost is not easily identifiable or known in advance of investing. Furthermore, it is nearly impossible to find after-tax rates of return for making apples-to-apples comparisons between various products and providers.

Most investment providers use the identical portfolio recommendations for investors’ non-registered accounts as they do for their registered accounts, as long as the account-specific risk tolerance is deemed to be the same. We can illustrate the cost of tax inefficiency by showing that modestly altering a portfolio, without materially altering the risk level or other characteristics of the portfolio, can improve the after-tax return of the portfolio.

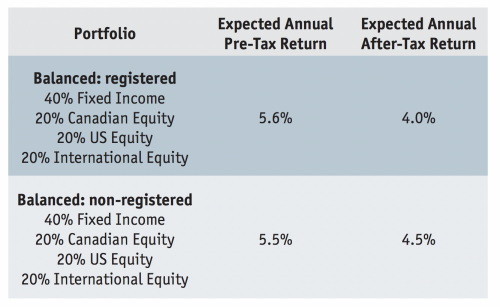

Consider an investor in Canada’s top marginal tax bracket, considered to have an average risk tolerance and invested in a balanced portfolio consisting of 40% bonds, 20% Canadian equity, 20% U.S. equity and 20% international equity. A reasonable long-term expected annual rate of return on this portfolio, on a pre-tax basis, is 5.6%. For a non-registered account, after applying tax rates to the interest, dividends (Canadian and foreign) and a conservative estimate for capital gains, the after-tax return on the portfolio is reduced to 4.0%.

By making some minor changes to the portfolio’s asset allocation, such as substituting preferred equity for corporate bonds (both considered to be fixed income) and finding investment securities that are innovatively structured to receive more favourable tax treatment, we can create a new portfolio that is very similar from a high-level asset allocation and risk perspective. The expected pre-tax return on this new, tax-efficient portfolio is slightly lower at 5.5%, but after taxes are applied, the return is a more favourable 4.5%.

Extending the analysis across the range of investor risk profiles (from Conservative to Aggressive) shows that the cost of tax inefficiency can vary from as low as 0.40% up to 1.00%. Remember that this is also an annual cost, which will have a compounding effect for the rest of an investor’s time horizon, making tax inefficiency very expensive!

In addition to the annual cost of tax-inefficient portfolio construction, there are other tax-inefficient practices to consider.

Any time that an investor decides to move investments from one financial institution to another, the investor will have to go through a formal transfer process. The investor will be given two options to transfer assets: “in-kind” or “in-cash”. An in-kind transfer will move the investments “as is” and will arrive at the receiving financial institution undisturbed. An in-cash transfer will require the relinquishing institution to sell all of the securities before transferring a single cash amount to the receiving financial institution.

The latter case of an in-cash transfer will result in the disposition of the securities, which is considered a taxable event. Depending on the amount of unrealized capital gains in the non-registered account, this could end up triggering a potentially large tax bill—one that could be avoided or deferred by requesting an in-kind transfer instead. Unfortunately, many financial institutions and advisors will not accept in-kind transfers because they are either unable or unwilling to provide the additional knowledge and effort required to effectively manage the transition of an investor’s assets from the current position to a new portfolio.

The cost of being unable to transfer an account in-kind will vary greatly from investor to investor, but we can try to illustrate the impact with a simple hypothetical example. Consider an investor with a $1,000,000 portfolio that has $400,000 of net unrealized capital gains. Assuming a 50% individual tax rate and applying the 50% capital gains inclusion, the investor stands to lose $100,000 in taxes payable due to capital gains if realized through a cash transfer. That is equivalent to a one-time negative 10% return!

Tax-loss harvesting is another tax-efficient practice that many investment providers do not effectively offer. Tax-loss harvesting is a strategy used to manage short-term tax implications for investors with non-registered assets. A tax-loss harvesting strategy is usually unique to an individual investor and, if coordinated properly, can have a material positive impact on wealth maximization over time. Implementing a tax-loss harvesting strategy requires a reasonable level of investment sophistication, and knowledge of the relevant tax rules concerning investment income.

Tax-loss harvesting traditionally takes place annually, usually towards the end of the tax year when an investor’s taxable position for the year is reasonably well understood. By selling one or more securities in the investor’s non-registered portfolio that have unrealized losses and purchasing different, but similar, securities in roughly the same amount, the investor can maintain uninterrupted exposure to markets while realizing capital losses. The losses can be used in the current tax year, applied to the three previous tax years, or carried forward indefinitely to offset future capital gains.

Conclusion

Despite what you might read or hear, investing is not “simple”, particularly when taxes are involved! While tax considerations should not be the only thing to consider (otherwise accountants would be considered investment professionals!), tax-inefficient investment management can be costly. In addition to the extra taxes payable annually on an inefficiently constructed portfolio, other tax-inefficient practices that prevail at too many financial institutions can result in potentially substantial one-time costs.

If you have a non-registered investment account and are considering moving it to a new investment provider, the first question that you should ask is if they accommodate in-kind transfers. If the answer is unequivocally “yes”, then proceed to your next question; if the answer is anything other than “yes”, then you may wish to consider moving on to the next candidate.

James Gauthier, MBA, CFA is Chief Investment Officer with Justwealth Financial in Toronto.