The Folly Of Zero

By "zero" I am of course referring to interest rates which, atrociously, have been pushed down not only to puny levels, but even in some cases, past the zero mark, down to negative levels.

By "zero" I am of course referring to interest rates which, atrociously, have been pushed down not only to puny levels, but even in some cases, past the zero mark, down to negative levels.

And when from these extremely low, zero or negative interest rates we deduct inflation and the inevitable fees and charges, we end well into negative territory.

Indeed, a UK bank has recently given notice to its business customers that they plan to start charging interest on commercial deposits.

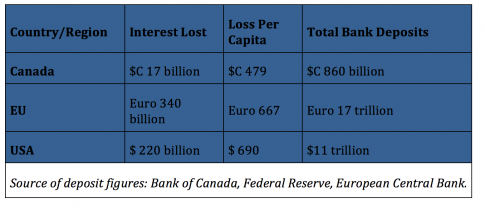

Now, if you look at bank deposits and assume that depositors should be earning at least 2% yearly, I have calculated that depositors are losing the following amounts each and every year by getting practically nothing:

This is serious money which is essentially going from the people who saved money to people who borrowed money — an imposed subsidy.

Borrowers Versus Savers

I spent most of my life advising savers and investors and managing money. I know that people who have money to invest rarely came to it by luck and that those who get lucky soon discover a foolish way to lose it.

Money is the result of hard work, producing the work you are supposed to do, wise and prudent risk-taking, creativity, entrepreneurship, and the discipline required to push yourself out of a warm bed before dawn on a wintry day to go out and work and do what you have to do. People who manage to put aside some money for investment do so by forgoing consumption, by not buying what they can do without, by spending wisely. And they do this day after day, week in and week out, for months, and years. Indeed, for a lifetime.

These good habits and these principles are what I and many others have been taught in school, and what our parents cajoled us into doing with that piggy bank which we could never pry open without getting caught. These are the good principles which built nations, the discipline of work well done, constant painstaking work, of hope in tomorrow, and of why you must heed Mr. Micawber's advice to David Copperfield and spend 19 pounds, 19 shillings and six pence rather than the whole 20 pounds (let alone even more, as is now the unfortunately habit of many).

Foolish

It all started in 2008, during the financial crisis, when monetary authorities were forced to push interest rates down sharply, flood the financial system with liquidity, and come up with new takes on old programs, such as “quantitative easing” under which central banks buy all sorts of bonds, including government bonds, from the market and indirectly print money to pay for them.

These actions saved the financial system from rigor mortis and utter destruction. But in the years that followed, starting around 2010 or 2011, interest rates should have started on the path towards normalization, not decreased further.

To be clear, it is important to point out that the objective of the monetary authorities has been to engender economic growth, whether real or via inflation, in order to grow the economy, increase the level of employment, and avert the risk of deflation. Interest rates are seen as an economic tool to generate growth.

Presented as being independent and tasked with economic growth, the heavy and thankless toll fell upon central bankers to foment growth and sprout greenery even in the most arid of lands. The problem is that the tools of central banks are limited to the monetary, that is, with the supply and cost of money. Governments have much wider powers, such as fiscal policy, dealing with public revenue and expenditure, and some are using them, but many have conveniently left the heavy lifting to central bankers.

Stimulants

Liquidity is a stimulant for all sorts of assets and markets. During the depths of the financial crisis, back in late 2008 and early 2009, I wrote a couple of articles for a popular financial website, SeekingAlpha.com, in which I argued that soon we might again see dividend yields going higher than bond yields, something which had not happened since 1959. Observing how bonds were behaving I also argued, in another article, that my conclusion was that, "The smart bond market does not believe that authorities around the world will have the political will power to eventually jack up interest rates as required and tighten monetary policy once the huge liquidity starts fueling demand."

Seven years later we are seeing just this. Interest rates have been cut down so far and for so long that the monetary authorities have now dug themselves into a hole in the sand. It is a quagmire of stimuli.

The US Federal Reserve, eventually, seems to be finding the courage to start raising interest rates in spite of the opposition it is facing. For most of 2016, its path was blocked by the Presidential election.

Increasing interest rates is exactly what we should be doing, gently and slowly, of course, and with pre-warnings, but this is now a matter of the greatest urgency.

Store Of Wealth

Money is not only a medium of exchange but also a store of wealth and, as such, can be converted into other assets.

The ancient Romans realized this and their jurists, amongst the most brilliant legal minds, argued that if a debtor does not pay a debt on time, the debtor ought to be charged a penalty, called "interesse". They argued that since money was a store of value, debtors had to pay on time so that creditors could have use of the money.

This is what economists nowadays call the opportunity cost of money. By lending money to you, what income from some alternative source am I losing? Interest, therefore, came to be seen in its proper secular light as being a charge for what the money would otherwise have earned. Interest is the price of money.

And the price of money, if money is to retain its value, is normally slightly above the true level of inflation.

Zero

In an era post the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions when we sing the praises of free markets and consider excessive market controls as remnants of the old USSR, we in the West have succumbed to strictly controlling the price of the most important asset in the world, money! And we have been doing so for much longer than is justified.

This price control, like most of the others which we experimented with over the ages, is pernicious and is damaging the very core of our financial system.

First, we must keep in mind that the price of any asset - of any ordinary share, of any bond, of any house, of any commodity - is determined not only by demand and supply but also by the level of interest rates.

As a consequence of zero interest rates, with money rendered unattractive to hold, most of the important financial markets have been pushed to historical highs: property in Canada, the USA, Europe and China, stock markets around the world, and bonds are now so expensive that many portfolio managers are shunning them, preferring instead to stay in cash or very short instruments.

Ironically, the solution to housing unaffordability, in my opinion, is not to slap on another tax but to start increasing interest rates to their normal levels.

Borrowing Binges

Low interest rates are also making it possible for governments, corporations and many individuals to borrow amounts well beyond what they are ever going to be able to repay! If servicing my debt costs me practically nothing, why should I not borrow as much as I can for terms as long as I can? Governments and corporations are doing precisely this. Since the financial crisis and the application of low interest rates, the overall maturity of debt has been getting much longer. Belgium and Ireland recently issued bonds maturing in 100 years at a low coupon.

Second, these borrowing binges will make it more difficult for monetary authorities to eventually normalize interest rates without increasing the danger of massive bankruptcies and government deficits – and borrowers know this, and therefore borrow even more, “secure” in their belief that the authorities are stuck between a rock and a hard place and “incapable” of raising rates. Talk of debt reduction programmes is now rare.

Third, certain corporations are raising money via bonds and buying their own shares on the stock exchange, effectively getting rid of shareholders. Debt is being substituted for equity.

Fourth, we can see that by their very own actions, the message which monetary authorities are communicating when they say that the economy is not recovering and that there is danger of recession and deflation and that the alternative use of money is to earn zero is a negative message, and a disincentive.

Fifth, when a company buys its own shares – and this is now so widespread that investment funds have actually been set up to invest in such companies – it will increase its earnings per share even if the amount of profit stays the same. Consider also that the interest charged for money borrowed is understated and this means that profits are being inflated. This also means that valuations will go even higher because markets value stocks on a multiple of earnings per share, the price-earnings ratio.

Penalizing Savers

Sixth, zero interest rates penalize savers and reward borrowers. The idea is to force people not to save and to consume! But since savers know that their hard-earned capital cannot earn them anything, they cut on their spending, not increase it. Those who have not saved, on the other hand, are forced to borrow, thus compounding the problem. This message by the monetary authorities goes directly against the principle of thrift. Also, if you can borrow, why work?

With house prices being pushed to the stratosphere and their savings earning nothing, savers who own their own home have been forced to borrow against it rather than retain the equity on their house and earn decent interest on their savings.

Seven, with interest rates at zero or negative, central banks have lost their main tool for stimulating the economy. And since they cannot raise rates quickly either, they have lost (or nearly) their ability to control inflation without damaging other aspects of the economy. In other words, monetary authorities – because this is not just about central bankers – have neutralized some of their own tools.

Furthermore, developments in recent years have also damaged many investment models, especially those of banks, insurance companies and pension funds. Banks have seen their interest rate margins shrink and, at the same time, are being forced to build up their capital. Institutional investors have also been forced to take on greater risk by substituting equities and other assets for low yielding bonds. This increases the instability built into the financial system and makes it extremely difficult for these institutions to properly fund and hedge for their future liabilities to pensioners and the insured.

Low interest rates are therefore exerting pressure not only on an individual’s perception of the desirability of thrift and on our working and saving culture, but also on the way institutional investors cope with their risks and obligations. Low rates are going to the heart of the financial system as we know it, and changing attitudes and behaviour for the worse.

Small and medium businesses cannot borrow on the market but must go to the banks and the banks have to assess the risk involved and price their loans accordingly. Their shareholders expect no less. So, while big corporations and governments can borrow at rates next to zero because of the artificial price control on interest rates, this spigot is not available to individuals and most businesses, albeit the latter can borrow a bit cheaper than they used to do. There is, therefore, an unjust dichotomy in the system which is pushing money into financial markets, governments and big companies but not to normal businesses.

Not only so but, finally, low interest rates are reducing the benefits of diversification by making most assets move in the same direction. Bonds, property and stock prices are now all high because the new money being created first finds its way into financial assets, and only later, if at all, into real assets and businesses.

Negative Rates

To my mind, as an operator, this prolonged and sustained push over many years by the authorities towards risk is today’s main source of systemic risk. This heightened risk has even spread to bank deposits and bonds due to bank “bail-in” procedures enacted by various governments, although under different pretexts.

How long and to what extent can this go on? I don’t know the answer but I guess for quite a long time until something – usually the least expected – snaps and we would have a new crisis, one which will probably dwarf all the previous ones.

History does not provide comfort: there were many instances in the past where debt was allowed to balloon and where people lost all their savings and many were so indebted that they chose popular leaders who simply promised them a debt jubilee whereby all debts were extinguished. History also teaches us that whenever there is a deep-rooted, prolonged, and widespread feeling of injustice, inequality, and corruption, the result is either revolution and war, a police state, or both, such as in Nazi Germany. We hope this time around things don’t end badly and that we see sense before it is too late.

As I hope to have shown here, there are many side-effects and collateral damage to zero interest rates and I feel that we are well past the stage where any future benefit is likely to exceed the continuous pernicious costs being incurred.

Gradually raising interest rates now is no longer about economic performance but about economic sanity.

Paul V. Azzopardi BA(Hons)Accy, FIA, MBA, CPA(MT) publishes ETFalpha.com, an investment newsletter, and has worked as a financial and investment adviser and manager for many years. He is the author of “Behavioural Technical Analysis” and other books. The views expressed here are entirely his own and not necessarily those of companies he is associated with. Email@paulvazzopardi.com